Number 22

October - December 1998

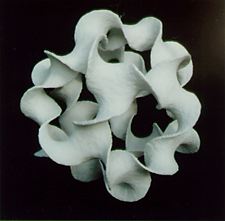

Battered Moonlight

1997

papier-mâché over steel

21 in.

CLICK ON IMAGE FOR MORE DETAILED VIEW

GEORGE W. HART

earned his PhD in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science from MIT.

He has worked there, and taught at Columbia and Hofstra Universities,

and is the author of a textbook on multidimensional analysis and

several dozen articles. While he has made polyhedra throughout his

career-since he was a boy, in fact-he has now, he says, become "a 'free

agent' of geometry," devoting his time to sculpture.

GEORGE W. HART

earned his PhD in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science from MIT.

He has worked there, and taught at Columbia and Hofstra Universities,

and is the author of a textbook on multidimensional analysis and

several dozen articles. While he has made polyhedra throughout his

career-since he was a boy, in fact-he has now, he says, become "a 'free

agent' of geometry," devoting his time to sculpture.

studioNOTES: What have you been doing recently?

This summer I gave talks at three great conferences

concerning math-related art: the Math and Design Conference in San

Sebastian, Spain; the Bridges Conference in Winfield, Kansas; and the

Art and Math Conference at UC Berkeley. And at New York Academy of

Sciences, on Oct 1, I brought a few pieces, showed slides of my work,

and discussed the pieces, the techniques, and their mathematical basis.

They were great opportunities to meet other artists and be inspired by a wide range of work. It was wonderful to show my pieces to such audiences, who are highly tuned into the mathematical aesthetic and strongly enthusiastic. At Berkeley, in addition to showing some sculpture and my slide presentations, I also gave two workshops on my model construction techniques.

The response to everything was so positive that I decided to make the plunge to full time. Last month I did what one is always advised not to do: I quit my day job.

What is the range in size of this work? Media?

My constructive sculpture is not tied to any particular

media. I try to use whatever materials best bring out the forms I am

interested in, usually woods, metals, plastics. So I spend a lot of

time working out the appropriate technique for each construction. I

just finished a three-foot piece assembled from hundreds of CDROMs.

They had to be slit, slid into each other, and invisibly glued. Thus I

worked out the techniques for a larger CDROM sculpture I have been

commissioned to install at UC Berkeley. I just finished a 20 inch piece

which is a mosaic of exotic hardwoods over a fiberglass core. It has

over 900 components. My largest so far is a 16 foot mobile hanging in

the student center at Hofstra University. It is made of hundreds of

plastic knives, forks, and spoons in various geometric arrangements.

But I want to go much bigger and am looking for appropriate commissions.

Do you think of these pieces as a series, a body, a group, or

just individual pieces? What do they have in common?

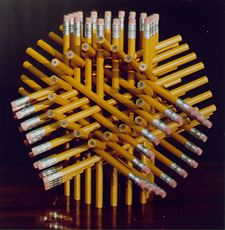

I have done a series which shares a certain "symmetry group."

This is a commonality which only a mathematician sees. To the casual

viewer they appear individual because of the different media: one is

oak and brass, one is aluminum, one is plexiglass, one is

papier-mâché, etc. In a few cases, I have made pieces

which are pairs, e.g., left and right handed.

Almost every one of your works consists of several identical

elements connected together to form a polyhedron. Why?

I don't honestly know. I find them beautiful, engaging,

challenging, worthy.

Could you describe your process?

My pieces start as visualizations. I am always imagining

forms and constructions of various sorts. When one is so strong that it

becomes an obsession then I feel I have to make it real. I often make

rough sketches as a guide, sometimes detailed drawings when I need to

work out some proportion or shape of a curve, but in other cases I know

precisely how I want to begin and just start building.

Most of my constructions require various jigs to form components or hold them in precise relative positions for assembly. I usually spend as much time making jigs that the viewer never sees as I spend in using them to make the piece itself. For jigs, I usually make precise sketches with dimensions and angles worked out.

About how long does a typical piece take, start to finish? Do

you work on more than one at time?

In the past, a month was typical for the physical work of

making jigs and then the piece. Before that might come days or years of

visualizing, mental design, sketching, and paper models. Now that I am

full time, I hope to pick up the pace. Usually I focus obsessively on a

single piece once I begin its construction, because I need to see how

it will turn out.

Are you sometimes surprised, despite all the preparation?

Yes, aren't all artists often surprised by the way their

things turn out? Sometimes I'm just delighted with how something I've

made seems so wonderful. (That sounds pretty immodest, but what can I

say; I like my stuff.) Other times, I am disappointed. Everything I do

is an experiment. I suppose it is results of the first type which keep

me going as an artist.

Is this mainly a question of how the materials you have

chosen will actually "work"?

That is a part, but also: I never even know that a piece is

even possible for me to finish until I'm done with it. Maybe I've made

a wrong angle in a component or something, maybe miscalculated and two

parts would have to be in the same place. Also, I design it based on

certain properties or views, and then see other views after it is

complete.

Is there any improvisation involved between the time the jigs

are built and the piece is finished?

Much. I'm always experimenting with different glues, clamps,

sequences of assembly, etc.

Your sculpture "Fire and Ice" has an interwoven band of

brass. Did you plan that from the start, or did you decide to add it

after you began constructing the wooden elements?

I knew there would be a woven brass sphere in the center. (I

was after the "texture" of old scientific instruments made of oak and

brass; they imply certain qualities to me that I wanted to import into

that sculpture.) I had two choices for its pattern in mind when I

started. To decide, I made a paper model of the wooden part, and wove

ribbon through it to see how it looked, e.g., how it lines up with the

openings in the wooden structure as seen from different angles. I chose

the one I liked, but still wasn't sure how it would appear in brass,

which is much stiffer and thicker. I had to guess what was the widest

band that wouldn't be too tight. Then there was the question of joining

the ends of the ten loops. I couldn't use a high temperature braze

because of the surrounding wood, so went with a low-silver solder and

had to figure out how to do it well, not heating the wood or dripping

flux on the wood, and then sliding things around to hide the joints on

the inside where they are hard to notice. That was one of my happiest

results, where I am very pleased with how it all came out.

How do you know when a piece is finished?

You mean if. I have quite a few things I am getting

back to someday, or so I delude myself, e.g., if I made the components,

but the jigs didn't line them up accurately enough so I have to go back

and redesign them, or something. Sometimes a piece is more work than I

can stand, and I put it off for something with a nearer term result.

For questions of how much to sand wooden surfaces, I just go by touch;

when I find it very sensual to fondle the wood, I am done.

To what extent does your education in math and engineering

influence your vision?